A mysterious ghost city

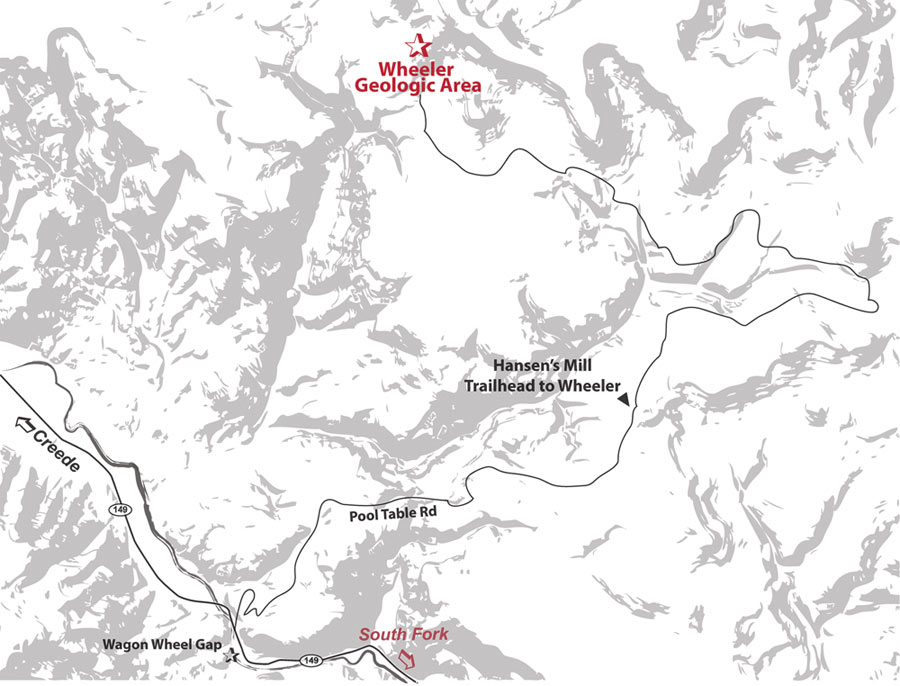

The Wheeler Geologic Area is one of the most fascinating geological features in the San Juan Mountains, located 2- miles east of Creede on the south side of the San Luis Peaks, or 24 miles from South Fork on Pool Table road. The geologic formations are contained in a tiny 60-acre section of the Rio Grande National Forest. In this area a mound of volcanic ash has eroded into a landscape that is so bizarre it seems to belong on another planet.

Know Before You Go

- This is an ALL-DAY trip. It will take 10+ hours to travel in, enjoy the formations, and get back out.

- The 14 mile-long road beginning at Hansen's Mill is extremely rough with deep ruts. High clearance vehicle (jeep with winch) or ATV recommended.

- Is the Road Open? Check Status of Rd #600 or call 719-657-3321 or 719 658-2556

- Check the Weather. Do not travel during monsoonal storms, as the road gets very slick and impassible.

- A 1/2 mile hike is required, beyond the end of the road, to get into the Geologic Formations

- Stay on the Trail! Going around obstacles widens trails, and causes erosion. Challenge yourself by staying on the trail.

- No camping or campfires inside the area of the formations.

- Buy a Search & Rescue Card ($3 online). The card helps reimburse local SAR team’s expenses for search and rescue missions

Wheeler Geologic Area resembles a mysterious ghost city, with spires and minarets that seem to float like a cloud above the surrounding mountains and evergreens of the national forest. This unique geologic phenomenon originated as part of the violent volcanic history of the San Juan Mountains and millions of years of erosion by the elements that carved the eerie landscape that we see today.

The San Juan Mountains are the largest volcanic area in Colorado. Enormous lava flows from volcanoes that existed 40 million to 30 million years ago coalesced into a composite volcanic field that was up to 4,000 feet thick and covered about 9,000 square miles. After a quiet period that lasted about a million years, the character of the volcanic activity underwent a dramatic change. About 20 million years ago great pyroclastic eruptions began to produce large quantities of volcanic ash. With major ash flow eruptions exploding again and again from 18 different volcanoes, building up a layer of volcanic ash that was up to 3,000 feet thick in some areas. Most of these pyroclastic eruptions ended about 26.5 million years ago. Sporadic volcanic activity continued until about five million years ago.

The Wheeler Geologic formations are a product of the period of ash flow eruptions. The debris was blown into the air during a pyroclastic eruption consisting of individual particles that range in size from dust flakes to a few scattered pebbles rarely more than a few inches in diameter. Occasionally broken rock fragments up to two or three feet in diameter, called brecci, were thrown out with the ash cloud. The ash particles settled back on to the groun din layers called volcanic tuff. Tuff particles are not firmly cemented together, so the relatively soft tuff beds are readily eroded by the wind and rain over millions of years. Most tuff is light gray or creamy in color, with a bit of pink and sometimes brown thrown in for good measure.

In the Wheeler area, the rains have carried away much of the smaller particles. Although a large rock will protect the tuff underneath it with the surrounding ash eroded away., esulting in a tall spire with a large rock balanced on the top as if a race of giants had sculpted the pinnacles and then balanced a rock on top of their sculpture. During cooling, the beds of ash often developed numerous vertical cracks. Erosion slowly widens these cracks, producing rows of ash columns that look like a parade of pale soldiers or huge ghosts. Some areas of ash are more solidly compacted than others, resulting in different rates of erosion that have produced many of the more peculiar shapes. Those who have written about the area describe the panorama of spires and pinnacles as forming castles, cathedrals and mosques.

The first recorded visit to the Wheeler formations was in 1907 when Frank Spencer, a Forest Service supervisor, and Elwood Bergy, a resort owner from Wagon Wheel Gap, followed up on rumors and located the place. Their enthusiastic report resulted in the designation of 300 acres around the area as the Wheeler National Monument. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the proclamation creating the monument in December 1908.

The name of the monument honors George M. Wheeler of the U.S. Army Corp of Topographical Engineers, who did extensive geological surveys in the area from 1873 to 1884. Although he got close to the area, there is no record that Wheeler actually observed the formations.

The Forest Service managed the monument until 1933, at which time jurisdiction was transferred to the National Park Service. However, because of its remote location and a lack of money there was no development of the site. In 1943 there were only 43 recorded visitors. On August 3, 1950 the Wheeler National Monument was abolished and the area once again became part of the Rio Grande National Forest. The Forest Service was sensitive to the need to protect this fragile area. In 1962 the protected area was increased from 300 to 640 acres and all mineral prospecting was prohibited.

In 1969 the improved gravel road that reached to within 14 miles of the area was constructed, but plans to continue the road to the actual geological formation were cancelled. It was in 1969 that the title Wheeler Geologic Area was applied to the protected 640 acre site.

The status of the Wheeler Geologic Area remained unchanged until 1993. On August 13 of that year the Colorado Wilderness Bill of 1993 was signed, placing a total of 611,730 acres in Colorado under tightly controlled wilderness management. One of the designated wilderness areas includes the Wheeler Geologic Area, comprising 25,640 acres in Mineral and Saguache counties. Wilderness designation precludes any logging, mineral exploration, road building, new water diversion structures or mechanized travel. Under the terms of the 1993 Wilderness Bill, the Wheeler Geologic Area received full wilderness protection.

Getting to Wheeler

The area is a wonderful place to see, but getting there requires a good bit of effort. The 14 mile, 4-wheel drive road to the area is quite rough and in wet weather it can get very slick and become impassable. Potential travelers are advised to check with the Creede Ranger District Office prior to making the trip. A visit to the Wheeler Geologic Area begins on Pool Table Road, which is a good gravel road that climbs to an elevation of 10,840 feet in about ten miles and ends at the site of the old sawmill referred to as Hanson’s Mill. Car travel ends at Hanson’s Mill, where the only remnants of the old sawmill is a huge pile of sawdust that continues to smolder with a deep fire that never goes out. The only amenities offered at this area are room for primitive camping and restroom facilities.

From Hanson’s Mill, the 4-wheel drive road is well marked, and designated as Forest Service Road 600. The road is a narrow corridor that is surrounded by the newly created wilderness area. The left fork can be driven for about a mile until the road ends and the 5.7 mile hiking and horse trail begins (Trail No. 790). The 4-wheel drive route goes straight ahead at the fork, beginning the long and bumpy 14 miles to Wheeler. The road is relatively flat, as the Wheeler site is only 300 feet higher than Hanson’s Mill. However, deep ruts and an unending succession of big rocks keep progress to a crawl. The 14 mile trip will often require three-to-four hours. The scenery along the route is so beautiful that stops for pictures and looking always slow progress. A variety of wildlife is common with deer, elk and coyotes rewarding those who keep a sharp eye on the surrounding forest. The last mile of the road winds through dense stands of fir and spruce, with deep ruts and narrow spaces between trees requiring some driving skills, when wet, this section of road becomes so slick that not even 4-wheel drive provides much control.

The road ends about a half-mile from the formations, where there are several nice spots to camp or have a picnic. A well-defined foot trail leads to the geologic area. After 200 yards, the trail divides; straight ahead leads to the base of the scenic area and a small rough shelter that was built around 1915. The left fork climbs around the west side of the formations to a spectacular scenic overlook that provides a panorama of the entire area. A small bench has been erected near the overlook. Visitors will need to be careful at the overlook and everywhere else you walk on the volcanic tuff. Erosion has formed canyons with steep walls. Many small round pebbles lie about the ash fields, resulting in treacherous footing much like walking on a floor covered with marbles.

A trip to the Wheeler Geologic area requires a long day plus strong legs, a horse or 4-wheel drive vehicle. At the end of the Wheeler Road #600 there are several dispersed campsites for the public to use. You are not allowed to camp or have campfires inside the area of the formations.